Campbell Core Technology: Data Logger Analog Measurement Uncertainty

by Kevin Rhodes | 更新日: 05/17/2018 | コメント: 0

Do you ever wonder about the uncertainty of your measurements? Occasionally, I’ll have a researcher ask how he or she can calculate the analog measurement uncertainty of a data logger. I usually direct the customer to the specification sheet that we publish. The customer then asks which statistical method we used to come up with the published accuracy. For example, did we use the Monte Carlo method or the three-sigma method? At first, I didn’t understand the question. (I guess that is what I get for choosing other elective courses and avoiding college statistics classes.) It took me a while to understand what the customer was asking, and I’ll explain why.

As a customer, you don’t have to wonder if your Campbell Scientific data logger falls outside the third standard deviation of our specifications. We guarantee that our data loggers will operate within our published specifications over our published temperature range. We tested them—every one—and they passed. While we do rely on statistical analysis to set accuracy expectations during the design phase of new data loggers, that plays no part in verifying the actual production performance of your data logger.

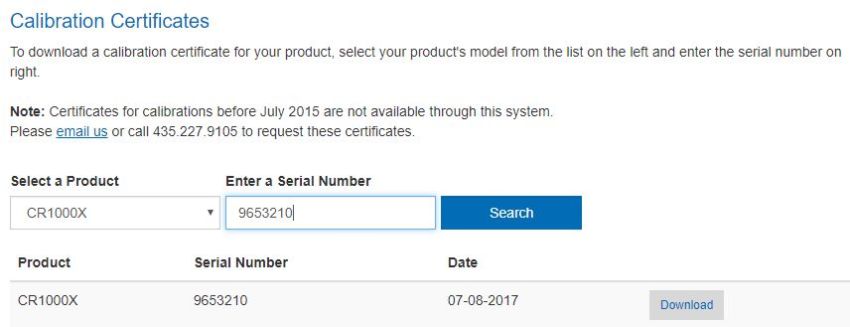

So, the question really being asked is this: how much does the data logger contribute to the measurement uncertainty? To calculate this, you should know that we use a "worst-case" method for creating our specifications and an "as-tested" method for each data logger. The "as-tested" information is found on the data logger calibration certificate available on your Campbell Scientific customer account, listed by data logger model and serial number.

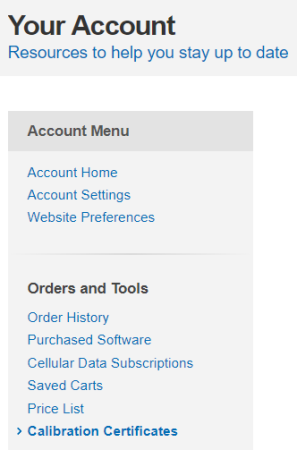

- To access this information, ensure you are logged in to our website, and navigate to the Your Account page. (For assistance, watch the "Certificates of Calibration" video.)

- Click Calibration Certificates in the Account Menu:

- Select the product from the drop-down menu, enter your product’s serial number, and click Search:

- Click Download to access your calibration certificate.

After reviewing your calibration certificate, you may be thinking that's all fine and good for when you first get your data logger and it’s brand new. But will your data logger remain in calibration over time?

In 2013, we decided to look at the analog measurement drift of our CR1000 datalogger to see if we could determine how often a customer should send in a data logger for recalibration. We hired a statistician to go through all our "as shipped" and "as returned" data. From this data, I discovered that, even though we were recommending a three-year calibration interval, we didn’t get many data loggers returned to us for calibration.

You might think that of the 100,000 CR1000 dataloggers we’ve sold, we would have a huge calibration data set. Well, we don’t. At the time of the analysis, we had sold 55,823 CR1000 dataloggers, and only 434 of those had been returned for calibration. This is equal to a sample population that is 0.78% of the total population. Despite the relatively small fraction of data loggers returned for calibration, the statistician assured me that 434 paired data sets were more than enough to produce meaningful results. The study calculated the drift between "as shipped" and "as returned" for ten voltage measurements on each data logger. The voltage measurements included a combination of single-ended and differential, positive and negative, across six voltage ranges from terminal one.

Since the 2013 study, we have continued to look for measurement drift as data loggers are returned for recalibration. The good news is that there continues to be a lack of correlation between the age of the data logger and drift in the analog measurements.

So, how do we get our data loggers to stay within the specifications?

- We design our data loggers with parts that have extremely low temperature drift.

- We calibrate each data logger over temperature.

- We have our own extremely stable voltage reference built into the data logger.

- We check this reference with every measurement or every few minutes, depending on the settings.

Yes, we check every measurement against a reference. Our Engineering Department calls this the "belt-and-suspenders" method (not in statistics books), which means that we use multiple procedures to achieve this constant adherence to specifications.

So, after reading all this, you may wonder why we still recommend calibration of our data loggers every three years. When measurements matter, it’s good to have both before-and-after calibration information for comparison. And, thanks in advance for helping us increase our sample population!

If you have a question or comment related to the analog accuracy of our data loggers, calibration, or drift, please post it below.

Kevin Rhodes (now retired) was a Senior Product Manager in the Environmental Market Group at Campbell Scientific, Inc., where he had been employed for more than 20 years. He was instrumental in setting the specifications for several of our data loggers and held a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from Utah State University. He contributed to our environmental sustainability efforts by frequently bicycling to and from work, which was of noteworthy distance.

Kevin Rhodes (now retired) was a Senior Product Manager in the Environmental Market Group at Campbell Scientific, Inc., where he had been employed for more than 20 years. He was instrumental in setting the specifications for several of our data loggers and held a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from Utah State University. He contributed to our environmental sustainability efforts by frequently bicycling to and from work, which was of noteworthy distance.

コメント

Please log in or register to comment.